| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 Allosaurus: RAAARRRHH!!!

2 Tyrannosaurus Rex: RAAARRRHH!!!

3 Other dinosaurs: RAAARRRHH!!!

4 Mercutio: Well, that was enlightening.

|

First (1) | Previous (2202) | Next (2204) || Latest Rerun (2861) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Shakespeare theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Death theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/2203.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Have you ever wondered about movie soundtracks? How they put them on to the movie film?

Have you ever wondered about movie soundtracks? How they put them on to the movie film?

You probably know that movies are printed on to long reels of film, which are run through a projector. (That is, movies that aren't projected with newfangled digital technology, which is still most of them.) One common movie film format is 35mm film - which is exactly the same size as the ubiquitous and popular 35mm camera film that we used to use before photography went all digital. Even now, when most people have converted to digital photography, you can still find 35mm camera film easily, in all photographic shops and most supermarkets. It's called 35mm film because it is 35 millimetres wide.

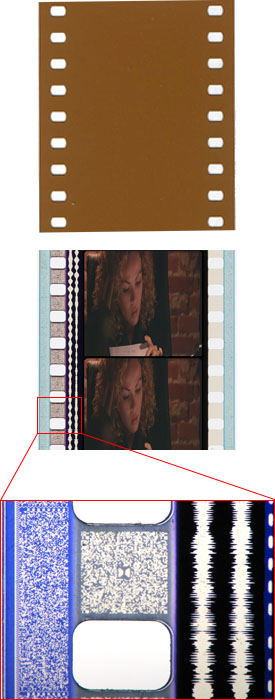

35mm film looks like the first image shown here, at top. This is a small piece - the film normally extends in a long strip, or roll, up and down as this image is oriented. The holes are sprocket holes, into which mechanical pins mounted on small wheels fit, and which drive the film forwards or backwards when the wheels turn. This is used to wind the film on in a camera, or to pull the film through a movie projector.

The second image shows what a piece of 35mm film looks like when it has a movie printed on it. Successive frames of the movie appear one above the other. You'll notice in this image that the picture is stretched vertically. This is how wide-screen movies are printed - it's called anamorphic printing. A special "anamorphic" lens on the movie projector stretches the image horizontally so it restores the correct aspect ratio and fills a wide-screen format.

Okay, that's the pictures. What about the sound? Where is that?

The sound is actually printed on the film, right next to the pictures. See the two wiggly white lines between the sprocket holes and the left side of the images? That's the soundtrack. It looks like the cross section of a record groove.

[Records, for those people younger than about 30 years old, were the precursors of compact discs. They stored sound information in finely scratched grooves on the surface of a vinyl disc, up to two and a half times the diameter of a CD. The sound was recovered by rotating the disc and letting a needle rest on the surface, scraping along one of the spiral grooves. The fine wiggles in the groove vibrated the needle at precisely the right frequencies to reproduce the intended sound, and electronics amplified the sound through speakers. Believe it or not, this stone-age-sounding technology actually worked, and kids in the 1970s and 1980s grooved to the latest music by this method. (This is where the terms "grooving" and "groovy" come from, by the way: record grooves. Seriously.)]

So, the wiggles in the soundtrack encode sound in pretty much the same way that record grooves do. Instead of being picked up by a needle, it's picked up by a small light that shines through the film. The white part of the sound track is actually transparent, and the amount of light passing through it changes as the wiggles run through the film projector. A light sensor picks up the variations in light intensity, and amplifies it and sends the signal to speakers. And there's your movie sound!

At least that's how soundtracks worked originally. Record grooves, and the soundtrack described above, are analogue recordings of the sound. Nowadays everything is going digital, for the reason that digitally reproduced sound can be cleaner and more resistant to things like scratches in your record (or on your film). So some years back, film studios began adding a digital soundtrack to films as well. Where did they put it? With the movie frames and the analogue soundtrack using up all the space in the strip between the two rows of sprocket holes, they stuck it in the row of sprocket holes, in between the individual holes.

See the pattern of dots between the sprocket holes? You can see it better in the enlargement at the bottom. Notice also the D and reversed D logo in the middle of the square - this is the Dolby Digital soundtrack. The pattern of dots is a digital encoding of the sound for this point in the movie. It's read in a similar way to the analogue soundtrack, using a light source shining through the film and projecting the pattern of dots on to a sensor. The sensor passes the data on to a Dolby Digital processor, which decodes the dots into the sound. Notice that this placement of the Dolby Digital soundtrack leaves the analogue soundtrack where it was. This is important for backwards compatibility with older movie projectors which still use analogue sound.

Now Dolby Digital is actually a fairly old digital sound technology. Several newer digital sound encoding schemes have since been invented, which have a higher data density, and thus a better sound reproduction. So there's reason to upgrade and add those too, while still maintaining backwards compatibility for analogue and Dolby Digital projectors. One new format is Sony Dynamic Digital Sound, or SDDS. Where can we put that, remembering it has to carry more data than Dolby Digital, so needs more space?

See the blue strips of dots running along the outside edge of both sets of sprocket holes? Yep, that's the SDDS soundtrack.

And then we want to add DTS, yet another digital sound format. By now, however, there's no space left to actually stick the required data on to the film. The solution is to include the DTS soundtrack of a movie as a separate digital file. The drawback of this method is that the sound is no longer automatically synchronised with the movie, by being printed right next to the frames where it occurs. You need a way to synchronise the sound to the pictures. Fortunately, there's just enough space left on the film to squeeze in one more tiny bit of data, in between the analogue soundtrack and the picture frames.

The narrow blue and white strip at the right edge of the enlargement is just a series of large dots, but that's all you need as a time signal to synchronise an external soundtrack. And that's how the DTS soundtrack is synchronised to the images. So this piece of film contains not one, but four completely different and separate sound encoding schemes, and can be used on any movie projector that supports any one of them. Pretty cool, huh?

This has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with today's comic. I just thought it was so interesting that I had an urge to share it.

The images are:

Which means that if I were to write this annotation now, I'd probably take the time to explain what a CD is, and not explain what a record is.

It's a curious world we live in.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |