| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 Serron: If we're going to deliver this cargo, we need an actual destination, not just a random vector and arbitrary travel time.

2 Paris: What's the second star to the right?

2 Iki Piki: Eta Cassiopeiae. Triana system, with a thriving commercial interstellar port.

3 Paris: And how long will it take us to get there?

3 Iki Piki: We should arrive by morning.

4 Paris: You were saying?

|

First (1) | Previous (3382) | Next (3384) || Latest Rerun (2868) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Space theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3383.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Last time we saw the Space crew, I was painstakingly cutting out the window regions in Photoshop and pasting in a background starfield. I wanted to find a quicker way.

In the past I experimented with putting printed pages of starfields (from an astronomy book) behind the windows, but I was never pleased with the results. So I took to the laborious method of editing in starfields after taking the photos, and used this for most of the original comic run. A problem with this is that sometimes the starfields look too sharp, given the depth of field of the camera. In that example, in the last panel Paris and Serron are in focus, but Spanners is slightly blurry, being further from the camera. By all laws of optics, the stars outside should be even blurrier, but they're not, because I pasted them in. So that meant later on I added yet another Photoshop step, of artificially blurring the starfield.

To sidestep all of this, for this strip I've tried something new. One problem with the printed starfield behind the window was that it had to be lit somehow, and the windows could cast shadows onto it. And when lit, the blackness of space doesn't actually look black, because printed blacks are really not very black - they still reflect a considerable amount of light.

So what I've done here is to put a starfield photo onto my iPad, and put that behind the windows, with bits of cardboard as shades to block any external light from falling on it. Because the iPad is self-luminous, the stars look like proper stars now, and the space between them looks sufficiently black. And because it's positioned behind the windows, they are blurred appropriately by the camera lens, and don't look sharper than the window frames.

I'm pretty pleased with how this method works, and with how much time it will save me futzing around in Photoshop. It also gives me a good excuse to put lots of different starfield wallpaper on my iPad.

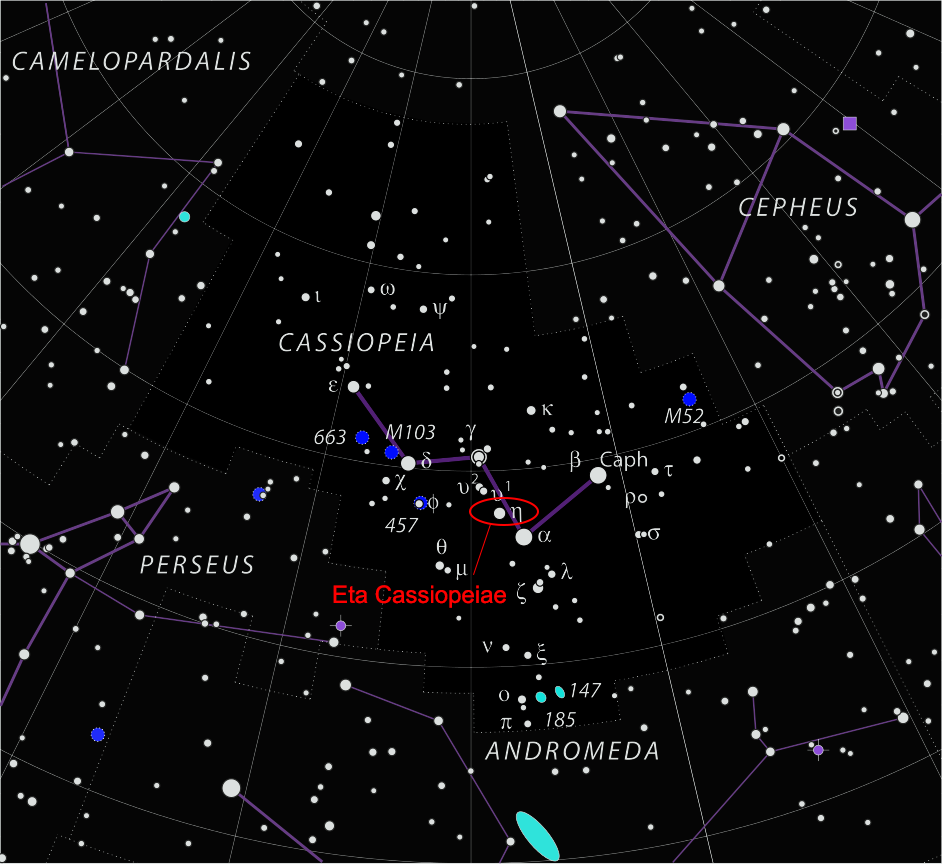

Eta Cassiopeiae, by the way, is a real star, just under 20 light years from Earth. If you live in the northern hemisphere, you can see it in your sky. (I, unfortunately, can't see it from Sydney.) If you know the "W" shape of Cassiopeia in the night sky - which I am led to believe is a thing that some people learn when they live in the northern hemisphere - then find the second downward point of the "W", on the "right" side (it could be on any side as you look up at the sky, because of the Earth;s rotation - I'm talking about the right side of the letter "W" as written). The star at the second downward point is Alpha Cassiopeiae. Eta Cassiopeiae is the slightly dimmer star immediately to the "upper left" of Alpha, towards the middle upward point of the "W".

Location of Eta Cassiopeiae. Modified from Creative Commons Attribution image by IAU and Sky & Telescope magazine, from Wikimedia Commons. |

The star's spectral type is G0 V, which is about as close as you'll get to our own suns G2 Vtype within 20 light years. Its mass is 97% of our own sun, and it is about 20% more luminous. Essentially, it's a very good candidate for a star "just like our own sun".

Eta Cassiopeiae is, however, a binary star, gravitationally bound to a smaller companion. This second star is of spectral type K7 V, meaning it is redder, and hence dimmer. It is a smaller star, with a mass only 57% that of our sun, and a luminosity just 6% of our sun. This does not mean Eta Cassiopeiae can't have habitable planets, however! The two stars are separated by an average distance of 71 astronomical units (AU) - 1 AU being the distance from the Earth to the Sun. Doing the gravitational maths, planets can have stable orbits about Eta Cassiopeiae with orbital distances anything less than 9.5 AU, which is roughly the orbit of Saturn in our own solar system.

So it's very possible that Eta Cassiopeiae has a planet orbiting in its habitable zone, where liquid water can exist on the planet's surface. Does it? We don't know yet. But perhaps one day in the near future we will know.

In the fictional future of this comic, it does have a planet - named Triana.

Oh, in our universe there's (most probably) no black hole anywhere near Eta Cassiopeiae. But remember how hyperspace works in this setting: The hyperspace generator "flips" the ship into an alternate universe, where the distances between points in that universe are non-linearly related to the distances between corresponding points in the original universe. So they flip into the alternate universe, fly until morning, then flip back, and they've covered light years of space in just a few hours. So presumably in the alternate hyperspace universe there is a black hole somewhere between them and Eta Cassiopeiae which they will need to fly around.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |