| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

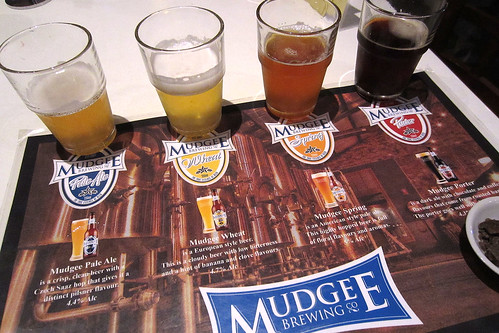

1 {photo of four sample glasses of different beers}

1 Caption: Beer

|

First (1) | Previous (3304) | Next (3306) || Latest Rerun (2874) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3305.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

The bar counter at Black Duck Brewery. Fermenting (steel top) and conditioning (white top) vats in the background. Jars of barley and hops in foreground left. |

Another thing I did was to visit the Black Duck Brewery and take a guided tour of their facility. I always enjoy behind the scenes tours, and industrial sorts of places can be just as fun as artistic and cultural institutions. The tour is fairly short, because it's a small factory, contained within a single large room. The brewer begins by sitting down at a table with you, with a set of glass jars containing the basic ingredients for making beer.

The first contains grains of barley, a bit larger than large rice grains. They are a pale, golden colour. The next jar contains malted and roasted barley, with the grains being dark brown. This is the first step in the brewing process. Malting is a process in which the grains are allowed to germinate by soaking them in water. This converts some of the starches in the grain into sugars of various types, which is necessary for the later fermentation.

The germination is halted by drying and heating the grains, and here is where the first differences in the brewing process can lead to differences in the end result. Heating the malted grain to higher temperatures can begin to roast it, making the grains darker and producing aromatic compounds related to caramelisation of the sugars, and eventually the distinct dark toffee notes bordering on "burnt" aromas and flavours. Lighter grains lead to lighter beers, both in colour and flavour, while darker roasts produce darker, more complexly flavoured beers.

Mash tun (centre left) for mashing the grain and kettle (centre) for boiling wort. |

Mashing lasts up to a couple of hours. Once the brewer is satisfied, the liquid is drained off into another container, called a brewing kettle. Most of the solid remains of the grains are filtered out at this stage, either using a mechanical filter or by draining the liquid through the mash itself, leaving most of it behind. In the kettle, the liquid, now called wort, is brought to a boil. This deactivates all of the enzymes, halts the production of further sugar, sterilises the solution of any harmful bacteria, and also boils off some undesirable volatile compounds such as sulphides (which carry a "rotten vegetable" aroma). Also during this stage, the flavouring ingredient of hops is added.

Hops are the flowers of the hop vine, specifically the female flowers. They have been used to flavour beer for centuries, perhaps thousands of years. Besides just tradition, adding hops adds a bitter flavour to offset the sweetness of the malt, as well as fruity notes that make a pleasing beer. Hops also acts as a preservative, inhibiting the growth of harmful microorganisms that can spoil the beer or interfere with the later fermenting process of the yeast. Next time you think of drinking beer as a stereotypically masculine activity, remember that beer is flavoured with flowers, just like chamomile tea or dandelion wine - and not even male flowers, just the female ones! Another flavouring commonly added to beer in historical times before the widespread adoption of hops, and still used for some specialty beers today, is gruit, a mixture of herbs.

A larger brewery: Little Creatures in Fremantle, Western Australia. |

Growing hops requires a cool climate, much like apples. While this is easy to find in the northern hemisphere, in Australia the growing region is restricted to Tasmania and the very southernmost parts of Victoria, which is about 1200 kilometres south of this brewery. So here they use the compressed pellets.

Boiling the wort takes about an hour. The hops can be added near the beginning or near the end of the boil, or in multiple stages, depending on the flavour profile the brewer aims to achieve. Earlier addition brings out more of the hops flavours and aromas. However some of the hops flavours are also in volatile compounds that are quickly removed by boiling, so if these are desired then at the end of the boil the hot wort is piped through a separate device known as a hopback. This contains fresh hops or pellets, and allows the hot wort to pick up the volatile flavour compounds just before being cooled.

The hot wort is cooled quickly to room temperature or just below by piping it through a heat exchanger. This is a series of pipes surrounded by a tank of cold water. Heat flows rapidly from the wort in the pipes into the cold water, which is pumped through to remove the now warmer water and replace it with colder water. From the heat exchanger, the now cool wort is put into a vat. The wort needs to be cooled quickly both to retain any volatile hops compounds and also to avoid a long delay in adding the yeast to begin fermentation.

Potters Brewery, Pokolbin, New South Wales. |

There are a few different methods of fermenting beer. The two main methods use different strains of yeast with different properties. One ferments at cool temperatures, around 10°C, and does so near the bottom of the fermentation vat. This type of yeast can completely break down all of the sugars in the wort (into alcohol and carbon dioxide), leaving a dry (i.e. non-sweet) style of beer, known as a lager. A different strain of yeast ferments at higher temperatures, around 20°C, and floats near the top of the brewing mixture, producing a foamy head as it does so. This yeast can only partially break down the sugars from the malted grain, leaving behind some types of sugar, which give the resulting beer a characteristic slight sweetness. It also produce esters, organic compounds such as those found in various fruits, which can give the beer subtle aromas and flavours of apples, bananas, pineapples, and various other fruits. The resulting type of beer is called an ale.

Chicha, corn beer home brewed in Peru. |

Lagers are typically matured at near-freezing temperatures for several months, during which the cool-temperature yeast remains still slightly active, adding additional alcohol and carbonation. Ales can also have a secondary fermentation during the maturing period, if a little fresh wort is added. At the end of the conditioning time, the beer is packaged in bottles or kegs for distribution and consumption. Even at this stage, a slight further fermentation can take place, resulting in what are known as "bottle fermented" beers. So the whole modern process of making beer takes several months, to perhaps a year or more.

Just before bottling, the beer is often filtered, to remove any last remaining solids and ensure a clear end product. Some producers choose not to filter the beer, simply allowing solids to settle out and then drawing the liquid off the top of the vat. This can result in a slightly cloudy appearance to the beer, which does not really detract from the taste, and can appeal to people interested in a "less processed" beer. The Black Duck Brewery I visited does not filter their beers, for example. In fact, depending on demand and current stocks of bottled product, they leave their beers to settle for different amounts of time, so the beer can come out with different degrees of cloudiness from batch to batch.

Schlenkerla brewery/tavern in Bamberg, home of Rauchbier. |

Ale is the older historical form of beer, since it could be fermented at room temperature, without needing any refrigeration. The exact process would have been a bit simpler than what I've described here, since the technology was less developed. But ale has a very long history, particularly in England, and also across Europe. In the medieval period, it became customary for people (including children) to drink ale with a low alcohol content, rather than water. This was a good thing for two reasons: firstly, ale has significant nutritional value, providing calories and some grain nutrients to people who otherwise had rather poor diets. Secondly, ale was actually safer than water to drink, because the boiling and fermenting process destroyed most of the harmful microorganisms that tended to reside in waterways near human habitation at the time. Such low-alcohol ales were known as small beer, an expression which can still be heard occasionally today. Also, to further shatter the image of beer as a masculine activity, most of the ale brewed in these times was done by women, in small cottage industry establishments.

Beer sampler at Mudgee Brewing Company, Mudgee, New South Wales. Yes, I seem to have visited a lot of breweries... |

You can do other things to modify beer as well. Rauchbier is a distinct smoky beer developed in the German town of Bamberg. It is made by smoking the malted barley before mashing. You can introduce various fruits or vegetables to the wort to transfer some of their flavours and aromas into the beer. During fermentation, various other strains of yeast can be introduced, either deliberately added or by exposing the beer to the air in open-topped vats. This is generally termed wild fermentation, and can result in strains of yeast that impart a distinct sour flavour to the beer, in a way similar to how sourdough bread differs from other breads.

Back to the brewery: after my tour of the brewing machinery, I tried sampling some of the beers. Black Duck brews a total of eight different styles of ale - they don't make lagers. They range from very pale and light to very dark and rich in heavy flavours. A sampler of four small glasses is available and I choose a selection across the range. The brewer pours them and arranges them from light to dark, recommending tasting them in that order. This is for the same reason that wines are tasted in a sequence from lighter to more intense - you can better appreciate the more subtly flavoured varieties when your palate is fresh, rather than soon after tasting something with a strong flavour. The four beers are shown in the title image, from left to right (though I drink them right to left): Phoenix (a stout style beer), Dark Ale, Heron's Craic (an Irish style red ale), and Platypus (an Australian pale ale). I offset the drink with one of the ploughman's lunch platters that they also sell at the brewery. It's a hearty meal including different types of cheeses, sliced meats, and relishes and my wife and I split it as our lunch for the day.

If you get the chance, I recommend visiting a brewery that offers behind the scenes tours and samplers of the various brews. The best bets are probably small boutique and craft brewers, rather than big national or multinational brands. Trying a wide variety of beers in a tasting session is a good way to get an appreciation for the differences in aroma and flavour, and finding styles you like. (A similar thing applies to wines, but that's a story for another day...)

It's also fascinating to learn just how much science is behind the process. Modern brewers are not rough and tumble characters with simple ways. Listening to our brewer go through the process of making beer, you realise he's talking in terms of complicated chemical and biological reactions. He needs to understand the interactions of all parts of this process to make the decisions that lead to various styles of end product, and that requires knowledge, experience, and creativity. As with many things, beer is both science and art.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |