| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of a tree branch with red and green bark strips}

1 Caption: Unbalance

|

First (1) | Previous (3293) | Next (3295) || Latest Rerun (2889) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3294.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

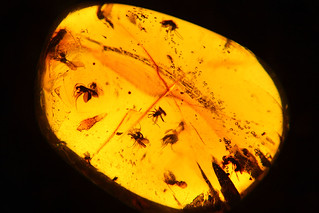

Amber, with insect inclusions. |

(For bonus points today, without reading any further, try now to guess the topic of today's discussion.)

Amber is a beautiful substance, radiant and warm. Unlike metals or stones, it is organic and, because of its heat conducting properties, does not feel cold to the touch. Pieces of amber have been used as decorations for thousands of years.

But amber has another interesting property. If you rub it on some wool you can start to hear a faint crackling sound. And then if you hold the amber near some tiny pieces of paper, the paper will leap up into the air and stick to the amber. The Ancient Greeks knew about this. The effect, as we recognise today, is that of static electricity. Our modern word electricity comes from the Ancient Greek word for amber: elektron. (I've discussed this before, when setting up to talk about chemical bonding. Today we're going in a different direction.)

Wool. |

This imbalance of electric charge causes certain effects. Positive and negative electric charges attract one another, so the wool and amber tend to become attracted to one another. But if you pull them apart, each object starts to attract other objects around it, such as little pieces of paper. This happens because the electrons in nearby objects shift around, moving away from negative charges and towards positive charges. Although each piece of paper remains electrically neutral overall, its charges are redistributed so that the part nearest the amber is now positive and so becomes attracted to the negatively charged amber. The result is that even though little bits of paper are normally electrically neutral, they are attracted to both negatively and positively charged objects.

The attractive force is also present with many other objects, but it is weak, so only very light objects like pieces of paper or hair strands actually move towards the charged object. You can notice it as the static cling of light clothing objects fresh out of the dryer, or styrofoam beads sticking to a cat.

Electrical sparks. |

Static electricity is one thing: when there is an imbalance in electrical charges. But this spark is different: it is the movement of electric charge. It is what we call an electric current, by analogy with a current of water. The electrons flow from one place to another.

An electric current is driven by an imbalance in electric charge. When one place is more positively or negatively charged than another place, then electrons in the more negative of the two places feel a force pulling them from there towards the more positively charged place. There is the potential for the electrons to move. This tendency for electric charges to move when charges are unbalanced is called, reasonably enough, an electric potential. Although you might not have heard of "electric potential" before, you are probably familiar with the units of measurement. Electric potential is measured in the units known as volts, and the difference in the amount of electric potential between two points in space is commonly known as the voltage between those points.

Measuring the electric potential difference of a mains power socket. DO NOT TRY THIS, it is EXTREMELY DANGEROUS. Public domain image. |

But electric charges are not free to move anywhere, in the same way that a massive object is not free to fall if there is something underneath it, blocking the way. Most things resist the passage of electric charges through them, including air. Usually, here on Earth's surface, the movement of electric charge means the movement of electrons. More broadly speaking, this is not always the case, as the movement of charged atoms, or ions, also counts. Charged atoms or other charged particles emitted by objects like stars, pulsars, and black hole accretion discs stream through space relatively unhindered, and these certainly count as movement of electric charge, but I don't want to concentrate on that today. Radioactive materials also emit highly energetic charged particles, which shoot through the air like tiny bullets. But putting these energetic processes aside for now, I want to concentrate on more sedate drifts of electrons, driven by electric potentials.

You can find electric potential differences readily in your home. Pick up a battery. The positive and negative terminals are at different electric potentials. The active and neutral contacts buried within your mains power sockets are also at different electric potentials. The potential difference, or voltage, of a battery is fairly small, the order of a few volts. The potential difference of a mains power socket is considerably larger, and so can impart a larger amount of energy. A battery is fairly harmless, and you can touch the terminals without a problem. But mains power carries enough energy to cause electrical damage to your body, which is why the metal contacts are shielded from prying fingers. (This is not the entire story - there is also a difference between the direct current (DC) voltage of a battery and the alternating current (AC) voltage of a mains socket, but that's for another day.)

The fact that battery and power socket terminals are metal, while things designed to protect you from the dangers of electricity are not is no coincidence. As stated above, most things resist the flow of electric charges, in this case electrons. But there are some materials which allow electrons to move easily through them. These materials have the property that their atoms contain full shells of electrons (I discussed atomic electron shells in #3276), plus a small number of extra electrons, to balance the number of protons in their nuclei. The few electrons not in full shells are rather loosely held by the atoms, and can slip freely across to neighbouring atoms of the same material. Get enough atoms like this together, and you form a bulk material which has billions upon billions of "loose" electrons, all sort of sloshing around amongst the underlying solid structure of the atoms. We call such materials metals. They include pretty much what you might expect: iron, copper, gold, silver, aluminium, tin, lead, and so on.

Not possible without electric potential. |

But you can put things other than just bare metal between electrical terminals. Some things you might want to try: light bulbs, television sets, toasters, washing machines, refrigerators, computers. Our electrical appliances are designed to connect to a source of electric potential difference and use the energy given to the electrons in them to do useful things: give off light or heat, or sound, or move things around, or perform other, more complex tasks for us. Different components within these devices variously restrict or switch the flow of electrons within them. The results can be amazingly complex, and depend on the details of interactions between moving charges and atoms.

Which will be a story for another day.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |