| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of the Lone Cypress, Monterey}

1 Caption: Making Atoms

|

First (1) | Previous (3279) | Next (3281) || Latest Rerun (2891) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3280.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Where did the atoms in this cheesecake come from? (Sorry I didn't have a photo of an apple pie.) |

It might seem like an odd question to ask. But now we know what atoms are and what they're made of and how they can be changed from one element to another by changing the numbers of protons and neutrons in their nuclei. The next most obvious thing about atoms is that they are all around us - in fact we are made of atoms. And there are all different sorts of atoms, from hydrogen with just one proton, up to atoms with scores of protons and neutrons, like uranium. In general, the lighter atoms such as carbon and oxygen and nitrogen tend to be more common than heavier ones such as bismuth and xenon and gold. Why should this be so?

Up until quite recently, we had no sensible way of answering these questions. They are almost the sort of questions that little kids ask and the only answer a parent can give is "because that's the way things are". But not quite.

The answer came about by trying solve what seems to be a completely unrelated (yet similarly "little kid question") problem. Why do stars shine?

This was recognised much earlier as a significant question that we might actually be able to figure out the answer to. Even before we knew that the sun itself was also a star, people speculated on what made it give off heat and light. For ancient peoples, the only similar thing they knew about was fire. So for some of them the sun and the stars were fires in the sky. Another interpretation was that the sun was simply a god, and the stars were the shining souls of great heroes.

A ball of fire? Not so hard to understand. |

Once you know the distance to the sun, which is a lot bigger than people thought it was, you can work out how much power it has to produce (how fast it produces energy) to give the heat and light we detect on Earth. It turns out that's also a lot bigger than anyone had imagined. Doing the calculations, scientists quickly realised that burning coal, or any other material, could not supply enough energy to power the sun.

It wasn't just our sun either. In the 1860s, Vatican astronomer Angelo Secchi did the experiments that confirmed that our sun was in fact a star, just up close. So all of the stars were producing these enormous, unfathomable amounts of energy as well. How were they doing it?

Do these get hotter as they shrink? |

Around this time, discoveries about the natural world were being made at an astonishing rate. The mysticism of alchemy had turned into the science of chemistry. Astrology had given rise to astronomy. And in biology and geology a revolution was still underway as people began to realise that the current state of the Earth and the living things that inhabited it was better explained by the Earth being hundreds of millions of years old, rather than the few thousand implied in a literal interpretation of the Bible.

The problem with the Kelvin-Helmholtz model was that when you did the sums, the amount of gravitational energy available was only enough to make the sun shine for about 10 million years. Something was wrong: either the new sciences of evolutionary biology and deep time geology, or the model's source of stellar energy. This inconsistency in the age of the Earth across different disciplines of science persisted for about 50 years.[1]

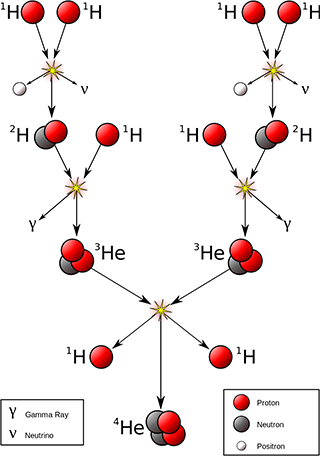

The proton-proton chain showing fusion of hydrogen into helium. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image by Borb from Wikimedia Commons. |

Nuclear physicists following Einstein and Eddington quickly worked out the details. We already knew from their visible light spectra that stars (including our sun) are mostly hydrogen, followed by a fraction of helium, then tiny traces of other elements. If only stars could fuse hydrogen atoms into helium atoms, the mass difference would provide all the energy they needed to shine for billions of years. But exactly how they could do this was still a bit of a mystery. A helium atom contains two protons and two neutrons, whereas a hydrogen atom contains just one proton. The ingredients for the overall reaction are four hydrogen atoms. Two of the protons need to eject positrons to transmute into neutrons, and the four nucleons need to come close enough together to stick into a single nucleus. But the odds of four individual atoms simultaneously coming close enough together that their nuclei can grab onto one another with the strong nuclear force are really, really low. So low that this type of reaction should almost never occur, even given as much hydrogen as a star, and under pressures and temperatures produced by its enormous gravity.

Nuclear reactions involving just two atoms colliding are much more likely. The trouble is, just two hydrogen atoms colliding cannot produce a helium atom. They form a nucleus of helium-2 (also known as a diproton), an incredibly unstable isotope which decays almost instantly back into two protons. The solution to this problem was worked out by Hans Bethe. He proposed that one of the protons could decay via beta-plus decay, emitting a positron and becoming a neutron. He followed up with calculations to show that a chain of intermediate product atoms could produce the required overall reaction in a plausible way.

First two hydrogen atoms fuse, with one proton ejecting a positron and becoming a neutron. This produces an atom of deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen. The deuterium atom at some later time collides and fuses with another hydrogen atom, forming the nucleus of a helium-3 atom: two protons and one neutron. This nucleus is stable, so can survive long enough to collide with another helium-3 nucleus. The resulting collision ejects two of the protons, leaving a stable nucleus of helium-4. Each step in this reaction produces energy and only involves a single collision between two nuclei, so can occur easily enough given the right ingredients and enough heat and pressure. This chain of reactions is known as the proton-proton chain.

So we finally knew what powered the stars. Other physicists calculated from the sizes and masses and luminosities of stars what the conditions of pressure and temperature were like in their cores. These are all consistent with nuclear reaction probabilities and rates. They also figured out other reaction pathways and other reactions that must take place inside stars. If there are small amounts of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in a star, there is a reaction cycle involving those elements, which also converts hydrogen into helium. This CNO cycle is important in very massive stars.

A star is like an onion. It has layers. Creative Commons Attribution image by Flickr user rosmary. |

This production of energy was the main thing holding the outer layers of the star up, preventing them from collapsing into the core under gravity. So the core of the star starts to collapse. As it does so, the pressure and temperature rise, as the atoms in the interior of the star get squashed closer together and start bouncing off one another faster with the additional kinetic energy. As this region of higher temperature and pressure grows, it starts to encompass regions further away from the core, where hydrogen is still more plentiful. When the conditions are right, the hydrogen around the core starts to fuse into helium.

So the star can continue producing energy for some time, fusing hydrogen in a shell around the core. But the fusion region is larger, and core is now hotter than before. The additional flow of energy outwards pushes the outermost layers of the star further away. Although the core regions where fusion is taking place has compressed, the outer layers of the star expand enormously. And although the energy being produced is higher, it is spread over a much larger surface area, with the result that the surface temperature of the star goes down. And since a star is an almost perfect black body radiator, a drop in surface temperature means the light it produces becomes dimmer and redder. The star has become a red giant.

Helix Nebula, a planetary nebula. The white dot at centre is the white dwarf star which produced the nebula shell. Public domain image by NASA/ESA from Wikimedia Commons. |

But eventually what happened to the hydrogen supply happens to the helium as well. It starts to run out and can no longer sustain the energy output needed to prevent further core collapse. A star about the mass of our sun cannot generate enough pressure in the core to fuse the carbon atoms there. So shortly after initiating helium fusion, the star no longer has enough temperature, pressure, or usable fuel at its core to continue fusing atoms. The nuclear fusion process stops and the core of the star collapses down into a tiny, hot ball of gas. The atoms squeeze closer and closer together until they are ultimately stopped by the electrons in their orbital shells pressing against one another. This is not a gas like we are familiar with, in which the atoms are free to move quite large distances and bounce off one another like ping pong balls. In the core of this dead star, the atoms hydrogen and carbon and so on are pressed together more closely than they are in a solid like a metal. The entire star ends up about 20,000 kilometres across - roughly the size of the Earth.

The star may be dead, but it's not cold - not by a long shot. The compression of material heats up the remaining core to a blinding white heat, well over 10,000 K in temperature. It radiates energy away as black body radiation of a cool blue-white colour. Such a star is known as a white dwarf.

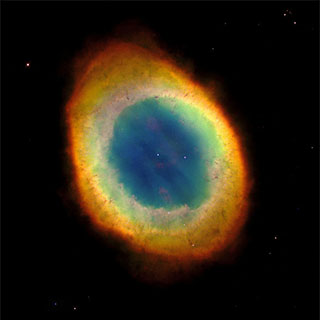

Ring Nebula, a planetary nebula, and the white dwarf star which produced it. Public domain image by NASA/ESA from Wikimedia Commons. |

The rate of energy loss of the white dwarf, although substantial, is small compared to the amount of thermal energy remaining in the star. So it can radiate visible light, without fusing any atoms and converting mass into additional energy, for a very, very long time. Longer in fact than its entire previous life as a hydrogen-fusing star. The dying ember of the star will still be radiating visible light for many billions of years. In fact, because the universe is only about 14 billion years old, and although many white dwarfs have formed, none of them have yet cooled down to the point where they stop glowing white hot. Eventually they will, and each such a star will become a cold, dark lump of compressed matter.

But some stars have a different fate. Stars larger than about twice the mass of our sun behave dramatically differently towards the end of their nuclear fusing lives. They do not stop at fusing helium into carbon. The temperature and pressure at the core can rise high enough to start fusing that carbon into heavier elements such as oxygen, neon, sodium, and magnesium. In turn, these can fuse into elements such as sulphur, silicon, and phosphorus. The chain of fusion reactions keeps going, supported by the intense conditions within the core of the massive star. For each successive reaction, the fusing atoms have higher mass than the product atom, so energy is released. In other words, the nuclear binding energy of the product atoms gets higher and higher. But this cannot continue forever.

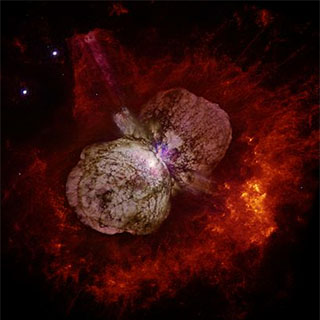

The star Eta Carinae (white spot at centre), and surrounding bubbles of gas blown off by the star. Eta Carinae is nearing the end of its life and will explode as a supernova probably some time in the next million years or so. Public domain image by NASA/ESA from Wikimedia Commons. |

When the core is laden with iron-56, there is nothing that can be done to release more energy. The iron is under so much pressure that the electrons of neighbouring atoms are squashed into adjacent quantum states. They can't occupy the same states because of the Pauli exclusion principle (mentioned previously here). This keeps the atoms apart and holds the core up against the tremendous pressure of the outer layers of the star. Lighter elements continue to fuse in onion-like shells around the core, providing the energy to hold those layers up for a final few thousand years or so. Meanwhile the core grows heavier with iron and the outer layers of the star have to squash down more and more to sustain fusion in the shells around it. Eventually a point is reached where the available electron pressure is not enough. The iron core collapses suddenly, the electrons being forced to combine with the protons in the nuclei to form neutrons, and nothing can stop it. The collapse from an iron core roughly the size of Earth to a ball of neutrons only 10 km or so across is so sudden, occurring within a second or so, that the outer layers of the star suddenly find they have nothing holding them up, and plummet into the core like an anvil dropped from a cliff. The outer layers of the star hit the neutron star core at a good fraction of the speed of light. There's still hydrogen and lighter elements out there, and the sudden compression initiates not the controlled trickle of fusion that can sustain a star for millions of years - but an enormous nuclear explosion.

The star blows up in one of the most violent and dramatic events in nature, a supernova explosion. The amount of energy released in an incredibly short time is enormous. A typical supernova can release more energy over a single day than every other star in an entire galaxy combined. But energy is not all it releases. In the incredible explosion, enough energy is available to cause all sorts of nuclear reactions, including the fusing of atoms into elements heavier than iron. In this way are produced elements such as copper, gold, lead, and uranium. And all of these get blasted out into space by the explosion. Following the explosion, a small dense core of the star is left behind. Depending on its mass, this can form a neutron star (which I've talked about a bit here) or even a black hole (which is a story for another day).

The elements blasted off by a supernova drift through space as clouds of gas and dust. The primordial mix of interstellar gas, before stars began forming, was almost entirely hydrogen, with a tiny bit of helium and an even tinier bit of lithium. But that was it. Essentially, the early universe was protons and alpha particles, which captured electrons to form hydrogen and helium. The first stars that formed were made entirely of this hydrogen and helium. But now, after billions of years, supernova explosions at the end of stars' lives have enriched that material with all sorts of other atoms. The clouds of gas and dust eventually condense into nebulae, then knots of material collapse under gravity to form new stars.

And around these new, second generation stars are rotating swirling clouds of heavier elements. This can condense to form lumps of iron and silicon and oxygen and carbon. Lumps we know as planets.

And on some of those planets (at least one that we know of, anyway) the elements have come together to form living beings.

So where do atoms come from? Where do the very atoms that make up your body come from?

The stars.

[2] If you've ever wondered "Just how important was Einstein anyway? Why is he so famous?", then you might start to understand by just how often in these annotations I lay out some problem in science, and then have to end up saying it was thanks to Einstein that we now know the answer. Frankly it's starting to get a little repetitive!

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |