| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of the Cape Otway Lighthouse lamp and lens}

1 Caption: Lens shapes

|

First (1) | Previous (3229) | Next (3231) || Latest Rerun (2890) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3230.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

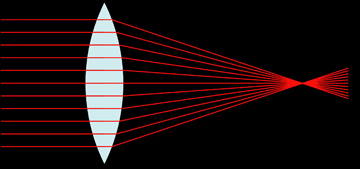

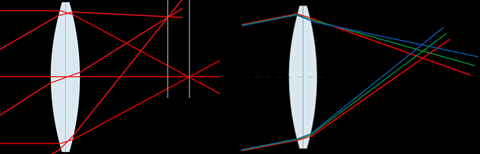

Figure 1. A converging lens. Adapted from public domain image by Wikipedia user Mglg from Wikimedia Commons. |

Most of the lenses we see around us are chunks of glass or clear plastic, with a typical "lens" shape, as shown in light blue in figure 1. Say the word "lens" to most people and this is what they think of. And for good reason. Not only is it a very common shape for lenses, but it's also shaped kind of like a giant lentil. You may notice that the words "lentil" and "lens" begin with the same three letters. This is not a coincidence. In fact, the Latin word for lentils, and the Latin genus name used in biological nomenclature for lentils, is "Lens". Is there some sort of connection here?

Indeed there is. Lentils were known in antiquity, being a common and nutritious crop in the Mediterranean and Middle East where early human civilisations arose. Lenses are a more recent invention. When you invent something, you need to come up with a name for it. A popular way to name a new thing is to call it by a name that sounds like something else that it looks like. Like the mouse attached to your computer has nothing to do with rodents, but was called a "mouse" because it kind of looks like one. And so it was with lenses. The first lenses looked like giant lentils, so they were given the same name (in Latin): lens.[1]

This sort of Lens-shaped lens is used for magnifying nearby objects. If you look through it at distant objects, you won't see them magnified, but rather upside down. What this sort of lens actually does to light rays passing through it is to bend them closer to the central axis of the lens (figure 1). We call this type of lens a converging lens, because if parallel rays of light enter it, they converge together. In an ideal converging lens, rays of light entering it parallel to the central axis would all converge such that they pass through exactly the same point on the other side. In other words, it focuses the light to a single point. This point is called the focal point of the lens, and its distance from the lens is called the focal length.

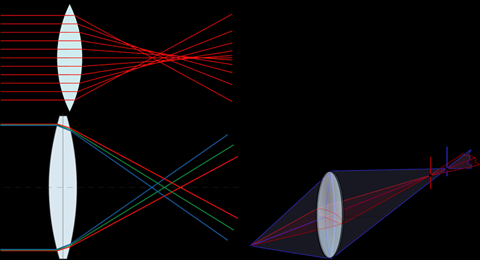

Figure 2. Spherical aberration; axial chromatic aberration; astigmatism. Adapted from: public domain image by Wikipedia user Mglg from Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike image by Bob Mellish from Wikipedia; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike image by Sebastian Kosch from Wikimedia Commons. |

A second way in which a lens can be less than ideal is if light of different colours (i.e. wavelengths, or frequencies) comes to a focus at different points along the axis. This is also very common, because the amount by which transparent materials bend light usually depends on the wavelength of the light. This is exactly the same phenomenon which produces rainbows, with water droplets in the air from rain or mist acting as tiny lenses. This effect is called chromatic aberration and manifests as coloured fringes around contrasting objects in the image produced by the lens. More specifically, this particular case is called axial chromatic aberration; there's another type of chromatic aberration, explained below.

A third way a lens can be imperfect is if light entering different parts of the lens parallel to the axis focus to different points, depending on the angle around the lens at which they enter. For example, if light entering the lens at the twelve o'clock and six o'clock positions focuses to a different point than light entering at the three o'clock and nine o'clock positions. This effect is called astigmatism, and occurs if the lens is not rotationally symmetrical, through a manufacturing error or for some other reason. The most common place we experience astigmatism is in the lenses of our eyes, which can become asymmetrical through the vagaries of biology. Like chromatic aberration, this is just one form of astigmatism; there are others that can occur, even in perfectly symmetrical lenses - if the light is entering at an angle, for example.

Figure 3. Field curvature; lateral chromatic aberration. Adapted from: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike image by BenFrantzDale from Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike image by Bob Mellish from Wikipedia. |

And if light entering the lens at an angle to the axis comes to different focus positions shifted laterally depending on the colour of the light, then that's the second form of chromatic aberration, called lateral chromatic aberration. This is the sort of chromatic aberration that photographers are most familiar with. It causes red fringes on one side of contrasting objects and bluish fringes on the opposite side, and it generally gets worse towards the edges of the image.

Imperfections in the shape of a lens lead to other sorts of aberrations which I haven't talked about. All of the aberrations I've described here can be (and usually are) present even in perfectly constructed lenses - that is, ones that exactly match their design specifications. The goal of designing a high quality lens such as those used for cameras is to combine multiple simple lenses to offset their various aberrations against one another, to try to cancel them out. With so many different types of aberration to balance, you can imagine that this is highly non-trivial. It comes down to a trade-off between minimising one aberration at the expense of allowing another one to be slightly larger than it could otherwise be. To make these trade-offs acceptable, modern camera lenses use upwards of a dozen separate lens elements inside them, of various curvatures and types of glass.

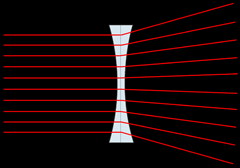

Figure 5. A diverging lens. Adapted from GNU Free Documentation Licence image by Wikipedia user DrBob from Wikimedia Commons. |

But let's imagine you're building a lighthouse, and you want to make a beacon that sends out a nice strong beam of light. The light comes from a point where the lamp is located, but it spreads out in all directions and quickly becomes faint and weak. To serve well as a lighthouse beacon, you want to pull the light rays closer together, so they go out in a tight beam. Essentially you want to make the light rays travel parallel to one another. So what you need is a converging lens. Being a lighthouse, you want a really big, giant converging lens, to make a big bright beam of light.

One option is the classic Lens-shaped lens. But make one of these two metres across and you're looking at an enormous chunk of glass, with a huge solid blob of really heavy material in the middle. This would make the lens really heavy - we're talking tons of glass here, literally. What can be done about this?

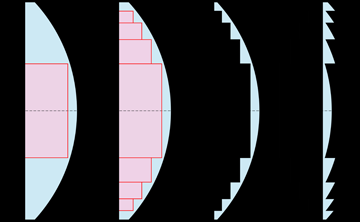

First let's modify the shape slightly, by making the back surface flat. We need to increase the bulge on the other side to compensate and maintain the same focal length, so this doesn't really save us anything. But now look at the big rectangular block of glass inside the lens, shown shaded in figure 5. (In three dimensions this is a cylinder.) A sheet of glass like this with both sides parallel doesn't do any bending or focusing of the light at all.[4] So... why not get rid of it?! If we do, the resulting lens focuses light in (almost) exactly the same way, but is now significantly lighter and less bulky. And we can repeat the process, cutting out cylindrical blocks of the lens that don't actually contribute anything to the focusing ability. What's really important is the angle between the back and the front of the lens, not how much glass is in between.

Figure 4. Development of a Fresnel lens. |

Fresnel lenses are really cool, because they work almost as well as big, bulky lenses, but can be made really thin and flat. This is how those "magnifying sheet" or "sheet magnifier" things work. They look like a thin, often flexible, sheet of plastic engraved with circular grooves. The grooves are carefully shaped to make up a Fresnel lens, with the result that the entire sheet acts like a giant magnifying glass. Fresnel lenses are also cool because they're in lighthouses, which are intrinsically cool in themselves.

Next time you travel somewhere where there's the opportunity to visit a lighthouse, and in particular to do a tour and go up to see the lamp, take advantage of the opportunity. Lighthouse lamps and lenses are impressive objects, and knowing a bit about the physics of how they work makes them even more interesting than just as a piece of unusual architecture. And if you're feeling really clever, you can even mention to the tour guide or lighthouse staff about the connection to lentils.

Even a lentil burger patty has the same shape as a lens! |

[2] And all members of your preferred romantic relationship demographic should be interested in physics and etymology!

[3] Some top-end camera lenses have non-spherical lens elements in them to reduce aberrations. You can tell which lenses have them because they are the most expensive ones!

[4] Light is bent inside the block, but emerges on the other side parallel to its original path. The parallel shift of incoming and outgoing light beams can be important in some cases, but is usually of little consequence.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |